Stories from Bukvy Readers for the Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holodomor

On the last Saturday of November, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Holodomor of 1932–1933 and the mass artificial famines of 1921–1923 and 1946–1947.

The aim of these artificial famines on Ukrainian lands was to destroy Ukrainian identity and ensure total subjugation of Ukraine.

Decades after the defeat of the Ukrainian Liberation Struggles (1917–1921) and the establishment of Bolshevik rule, Ukraine still witnessed frequent and mass protests against Russian emissaries and collaborators.

In August 1932, Stalin wrote to Central Committee Secretary Lazar Kaganovich, expressing concern that the Soviet Union “might lose Ukraine.” Remembering Lenin’s earlier directive that “without Ukrainian bread, Soviet power in Russian provinces is doomed to collapse,” the Soviet authorities resolved to solve the “Ukrainian question” once and for all and secure their dominance.

Today, Bukvy shares the memories of our readers and their families about this crime perpetrated by the Russian regime against the Ukrainian people.

We are deeply grateful to everyone who shared these everlasting pains with us. Eternal memory to those killed for wanting to remain Ukrainians and live on their native land.

Yevhen Chubuk

In one of the graves in Zghurivka, Kyiv region, lie two victims: one of political repression and one of the Holodomor.

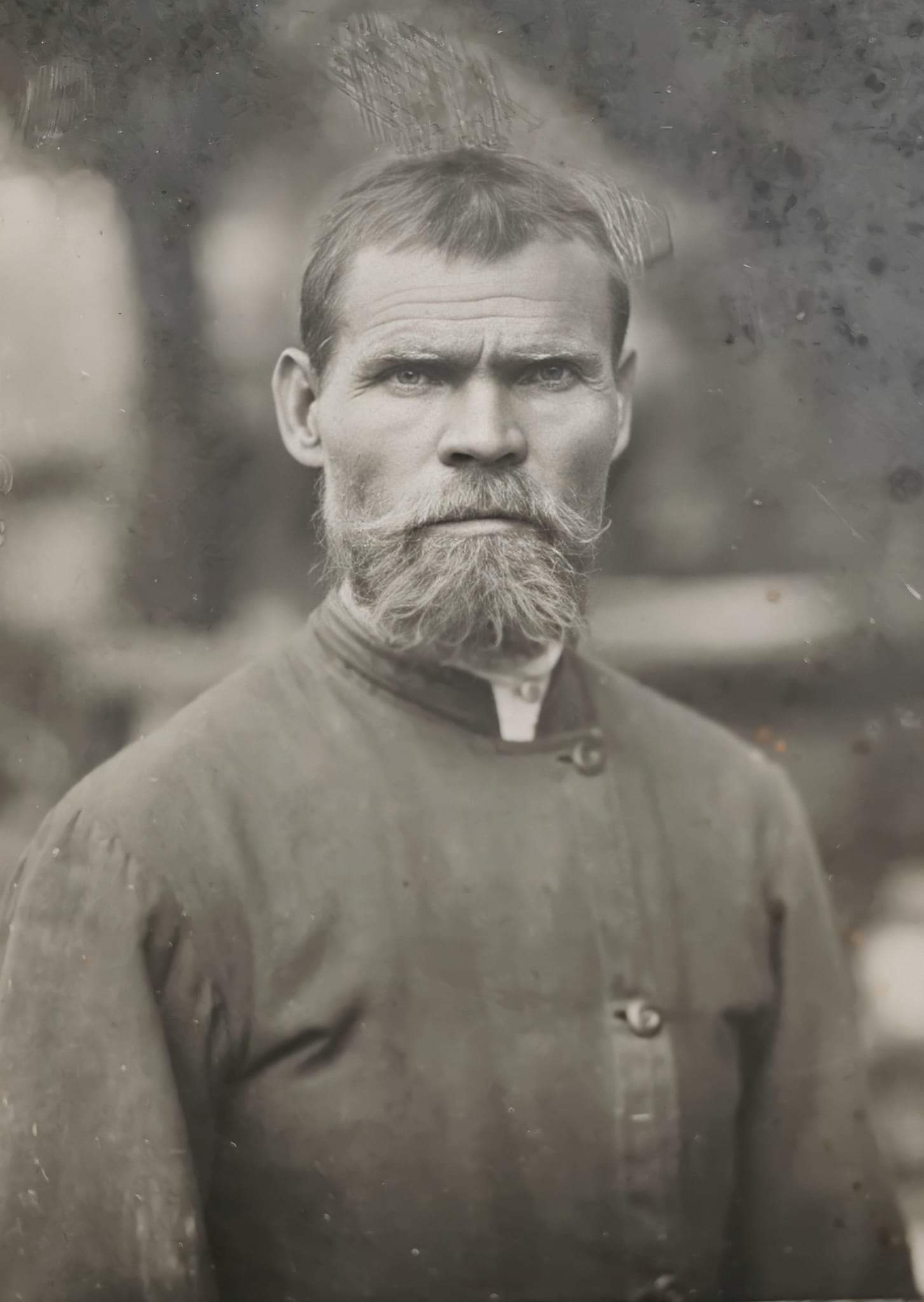

The photo shows my great-great-grandfather, Tymofiy Danylovych Psyk (1870–1933). He was a freeholder, working hard on his God-given Ukrainian land to grow wheat, as had six generations before him.

Everything changed when death and famine—symbolized by the sickle and hammer—arrived in Zghurivka. The Soviet totalitarian machine and local collaborators branded him a kulak and “enemy of the people.” In 1930, everything was taken from his family: land, livestock, a mill, and farming tools. Despite this, Tymofiy refused to join the collective farm. As a respected farmer, his example inspired many other individual farmers to resist.

This defiance was unforgivable to the Soviet regime. Nearly three years later, local Communist activists summoned him to the village council and brutally beat him. He succumbed to his injuries in 1933.

In the same grave at Zghurivka’s Cossack cemetery lies a woman who starved to death during the Holodomor. At the time, many families lacked the strength to bury their loved ones. Bodies were left on the streets or at cemeteries.

Recently, I discovered that this woman was also a relative of ours, descending from the Ivchenko Cossack lineage.

Thus, in a single Zghurivka grave rest victims of both the Holodomor and political repression, killed for their pursuit of freedom, love for their homeland, and Ukrainian identity.

In 1991, Tymofiy Danylovych Psyk was officially rehabilitated as a victim of political repression. His daughter Pelageya (my great-grandmother) buried her own child, who starved to death, in their backyard in Zghurivka.

The Holodomor, as a genocide of the Ukrainian people, touched every Ukrainian family, including mine. It claimed not only those who lived but also those who were never born. We lost millions of Ukrainians who could have built a thriving nation.

I remember. I will never forgive. And I will pass this memory to future generations.

Yevhen Chubuk, farmer, Zghurivka native in ten generations.

koval_kova13

During university, I participated in folklore collection and recorded a story from my great-grandmother about the Holodomor. She recalled how her mother would take her and her younger sister to a nearby town to a children’s shelter so they could have at least one meal a day. There was no food at home—only unbearable hunger.

The journey led through a forest, and winters were harsh. With no shoes, they walked barefoot through snow and frost. One evening, as darkness fell, they saw something approaching, moving without legs, as if floating. My great-great-grandmother began to recite the “Our Father,” and the apparition disappeared. All three of them saw it.

They were so hungry they hallucinated. My great-grandmother didn’t specify how often they were brought home from the shelter, but there they had at least bread and water. Many children fell ill and died of starvation. Behind the shelter was a mass grave filled with handmade crosses without names.

My great-grandmother survived, but her sister did not. Her burial site is unknown.

Another story tells of a child disappearing in our village. The mother went to a neighbor’s house to beg for food, only to find her missing child’s fingernails floating in the pot of stew.

Writing this, I want to scream from horror…

Inessa Yaroshenko

I want to share a story about the Holodomor in the Kyiv region, Tetiyiv district.

My late great-grandmother was born in 1926 in the Kyiv region. She lived through many difficult historical events, but the most horrifying for her was the Holodomor of 1932–1933. She said it was the most terrible year of her life. She and her two younger brothers survived by a miracle.

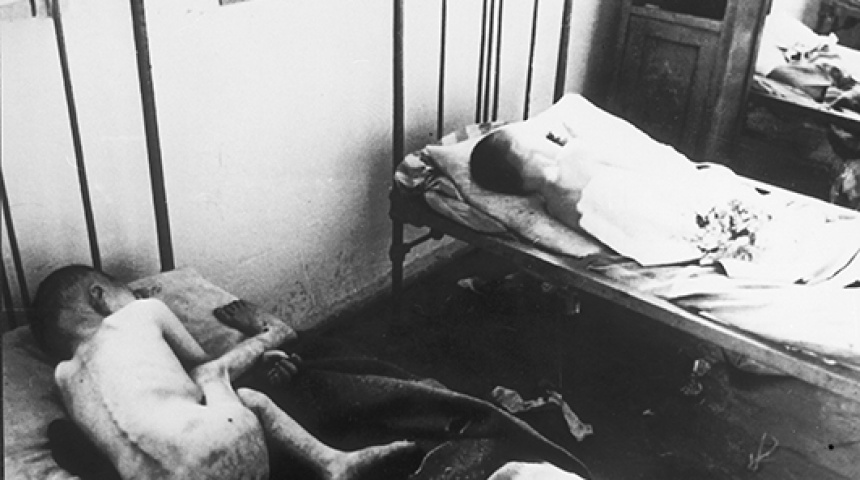

She recalled that people in uniform would constantly come and poke the entire yard — the ground, walls, roof, and tree stumps — with metal rods. They took everything they found. Little children cried and begged for food, but there was none. Their mother went to a sugar factory and scraped old, foul-smelling beet pulp from the pit. She made patties from it and baked them in the oven. When the children greedily began eating them, they found the food revolting and stinking. After eating those patties, their stomachs became terribly bloated, and they couldn’t stand up. Their hands and legs swelled, and their heads became so heavy they couldn’t lift them.

She also told us about a cart that roamed the village, collecting the dead with pitchforks. One day it would go down one street, the next day another, taking bodies to a mass grave. Sometimes, a person who was still alive but too weak to move was mistaken for dead and loaded onto the cart. Even if they screamed, “I’m still alive!” they were told, “We won’t be back tomorrow,” and taken to the grave with the dead, buried alive under the weight of corpses.

They ate anything: weeds, seeds from plants, frogs, bark from trees. All the cats and dogs in the village were eaten, and acts of cannibalism began.

Winter that year was unimaginably harsh. Only God’s mercy allowed my grandmother and her brothers to survive.

When spring came, the children, barefoot and in rags, ran to the fields, scraping away the snow with their weak hands to find the first shoots of grass.

This story I heard hundreds of times from my great-grandmother Pavlina. She always ended with, “May there never be hunger or war again!” But unfortunately, the oppressors have returned, seeking to throw us into the same pits.

Olena Andrushchak

A story about the Holodomor. This happened in the village of Khalaidove, now part of the Uman district.

My grandfather, Moroz Petro Stepanovych (1889–1974), and grandmother, Moroz Agafiya (Hapka) Lazorivna (1901–1967), had 11 children, but only five survived. In 1933, three children—Vasyl (b. 1921), Pylyp (b. 1927), and Vanya (b. 1933)—died of hunger in one week.

Grandmother had no milk to feed the youngest. For the older children, she walked around the village with a cup, begging for milk. The family, once wealthy with two cows and a pair of horses, had been left with nothing when everything was taken to the collective farm. They were allowed to keep only a heifer, which they had to slaughter and bury in the yard in the fall of 1932.

Members of the local communist committee came and poked everything in the yard with rifles. They found a bag of peas in the barn and took it. They seized a pot of beans from the oven and smashed the pot of borscht, spilling it. Grandmother became so distraught that she stopped producing milk.

The children lay on the stove with swollen legs and bellies, begging for even a small piece of bread, but there was none. Only Antosya (b. 1923), Marika (b. 1929), and Mykola (b. 1931) survived. The girls gathered rotting potatoes from the field and ground lamb’s quarter seeds to make pancakes on a dry skillet.

After the Holodomor, the family had four more children: Dimna (b. 1937), Sasha (b. 1939, died in 1940 from tuberculosis), Pavlo (b. 1941), and Melanya (b. 1942, died in 1944 from measles).

In 1947, Mykola, still very young, went to Western Ukraine to work. He returned with half a sack of grain, saving the family.

How can such things be forgotten?

I began teaching younger students during Soviet rule (since 1983). There wasn’t a single mention of the Holodomor in any textbook for younger students. Only in the textbook Reading for 3rd Grade in 2003 did a story called Bread appear. After reading it, I asked my mother about those dreadful times.

Unfortunately, no photos from that period have survived.

Vladislava Chorna

1933, Cherkasy region. The Holodomor. At that time, my great-grandmother Paraskeva was 13 years old, and her younger brother Oleksandr was only three. Their family of five included three children and two adults.

One day, they received horrifying news: something had happened to Oleksandr. Paraskeva ran to him. He was lying on the ground, convulsing, with foam coming out of his mouth. She picked him up, but within minutes, he passed away.

It turned out that while everyone else was working, the hungry and defenseless three-year-old had found some deadly nightshade berries nearby and eaten them. Paraskeva watched him die in her arms, unable to help.

The family managed to survive the Holodomor by a miracle, as cannibalism was rampant in their village. Their father risked his life to bring food from Kamianets-Podilskyi, where he worked. By some miracle, he smuggled flour past the blockades and shared it with the family.

My great-grandmother Paraskeva lived a long life—81 years—but the pain of losing her brother haunted her until her last days. According to my father, she would often sit by the window in the evenings, crying as she remembered that tragic day and the events of 1933. Her grief never healed.

In 1941, during World War II, Paraskeva’s older brother was taken to Germany. He attempted to escape twice but ultimately died in a concentration camp.

I first heard this story when I was 13, and my little brother was three. Looking at him, I couldn’t imagine the unspeakable pain my great-grandmother endured. This story etched itself into my memory more deeply than any other tragedy our family experienced during the Holodomor era.

I like to believe that now, Paraskeva is reunited with her little Oleksandr, in a place where there is no hunger or fear, along with their older brother. Rest in peace, dear grandmother.

gloriana_of_kyiv

My great-grandmother Zoya, originally from the Donetsk region, had a husband and a daughter named Liliya. However, in the 1920s, her husband was executed by the communists as a “kulak” because he made felt boots and owned a lot of wool, which was considered valuable at the time. Great-grandmother was left alone with her child.

She often told my grandmother a story about her neighbor: when people were already exhausted from hunger, they agreed that if Zoya knocked on the window, the neighbor would turn her head as a sign that she was still alive. One day, Zoya knocked and knocked, but the neighbor didn’t turn her head.

During the Holodomor, my great-grandmother not only survived with her daughter but also took in two orphans—both named Ivan. When I used to visit Donetsk, my great-grandmother and her children lived on a small plot in a tiny house with an annex.

I have almost forgotten their faces. Ivan and the other Ivan, as far as I know, have already passed away. Zoya as well—she died before 2014. Now only Liliya is alive, but she is of a very old age.

My grandmother herself felt the effects of hunger—throughout her childhood, she ate only pies, buns, and pancakes. She passed this story down to my father, and that’s how I learned about it.

sociofilka

My grandmother’s family were Lemkos, but even so, she never allowed bread crumbs to be thrown away. When I was very little and lived with my mother, grandmother, and her aunt, that aunt would always hide a loaf of bread under her pillow.

I don’t know the full history of my mother’s side of the family, but these are the memories I have.

Reading the memories of others makes me feel such pain for all these people. It’s terrifying to think of how Ukrainians were turned against Ukrainians, how parents ate their children, and vice versa. It’s horrifying to know that our executioners orchestrated all of this…

10.10_d

My great-grandmother survived the Holodomor and recounted how terrifying it was. They hid ears of wheat for a “black day” and survived by catching field mice and snakes to eat. If they had a small piece of lard, they would dip it in water to make the soup a little fattier. They would dip it and immediately take it out, then hang it in the chimney.

Some people ate small children. They ate bark from trees…

inka.innochka

Our great-grandparents were from the Lviv region. The Holodomor barely affected them, but my grandmother remembers to this day how “black people” came to them from Central Ukraine: thin, starving, barely moving, begging for a piece of bread and some milk, unable even to chew. Those were horrifying years because what they told us was beyond comprehension. Could it really be that Ukrainians (under Moscow’s direction) could destroy other Ukrainians like that?

cult_tela_odessa

My great-grandmother, great-grandfather, and their family of five children were from the Mykolaiv region. My great-grandfather worked on a collective farm, which saved their family. Grain was confiscated, and people were forbidden to leave the village (in cities, it was possible to survive and find work). When officials came to their house to take the grain, my great-grandmother sat all five children on a chest and said, “I won’t give anything away.”

My great-grandfather pushed the children off the chest and voluntarily handed over the grain. Then he loaded the family onto a cart (which was difficult because they were taking away horses and livestock as well) and moved them to Odesa. That’s how we became Odesans. In the city, he worked in construction. Thanks to this, the family was saved. This is almost an exceptional case because usually, everything was taken away, and leaving the village was prohibited. In 99% of cases, people died. The Soviet government always and everywhere killed its own people. I don’t understand today’s nostalgia for the Soviet Union. Have you forgotten? Or lived in a different reality?

boichenkoart

In my grandmother’s family, all the children survived. She had 13 brothers, most of whom died during World War II. My great-grandmother was slightly wealthier than other villagers and constantly traveled to Kyiv to trade her jewelry, mostly for flour. That’s how they survived. My grandmother’s most haunting memory was the hungry eyes of the neighbors. She wasn’t even allowed to leave the yard.

yuliyavowk

My great-grandmother was the eldest child in the family. As a child, she often recounted one day of her life: “When winter ended, and the snow melted, Mom made pancakes out of weeds and gave one to each child. She was happy that all the children had survived the winter, which meant we had made it. We all hungrily ate except for the youngest brother. He took the pancake in his hand and immediately placed it back on the table. That was the last day of his life…”

I was very little and dreamed of traveling back to the times of the Holodomor to give her little brother a piece of bread before the snow melted.

asya.dan

My great-grandmother’s brother was declared a “kulak” and exiled to Siberia. He left his three children with my great-great-grandfather because children couldn’t survive on the trains. Later, he took them to Russia when they grew older. The descendants of those children still live in Russia and tell us to be patient—they’ll “liberate” us soon.

Sofiya Steblina

My grandmother was born during the Holodomor.

I know her mother (my great-grandmother) made food from plantain leaves and other grasses.

She not only saved her child but also helped others survive.

kseniya__v__malysheva

My great-great-grandfather disappeared when he went searching for work in neighboring villages in the Poltava region. He left with a fellow villager. They saw a yard with a sturdy fence and dogs. My great-great-grandfather went into that yard, while his companion moved further into the village. They agreed to meet in the evening.

The companion waited for him but never saw him again. He encountered an old woman and asked, “Man, what are you doing here?” He explained he was waiting for his friend. She told him, “Run away from here! They’re selling human meat in that yard!” The companion fled, but my great-great-grandfather never returned.

_im_summerday

My grandmother had seven siblings. All of them, as well as her parents, died during that time. She was the youngest. During World War II, she lived in an orphanage. At 15, she married a 43-year-old man to survive. She worked hard her whole life at a sugar factory, carrying heavy sacks. She always picked up crumbs and said, “This is bread. Every crumb is important.” Rest in peace, Lydia.

dasha_g_s

My grandmother said their mother made pancakes from frozen beets. She worked on a collective farm and would steal a handful of wheat. That’s how they survived: three children and their mother.

mirkel9

As a child, my grandmother collected mussels in a pond. They boiled them at home, and that was their staple food. Any leftover bread was hidden in clay. It was all terrifying…

dianaonishchuk7

My grandfather was the only one of four children to survive the Holodomor. The youngest, who was still in the cradle, died because their mother, who was collecting ears of wheat, was thrown into a cellar where 200 people were locked without air until they suffocated. She miraculously survived. When bodies were being pulled out with pitchforks, she groaned. Those handling the bodies simply tossed her aside. That’s how she lived. I also know that one of the brothers was eaten. He looked plump and never returned home.

My grandfather never wanted to talk about it or remember it. He was very traumatized. He worked tirelessly and made everyone around him work too. He kept three cows, planted potato fields, and preserved everything he could, making 300 jars of stew. I always wondered as a child why he made so much. Now I understand—the fear of hunger drove him to stockpile such enormous reserves.

millellen

My dear grandmother Anastasia survived the Holodomor, being the only one in her family to live through it as a child. I don’t know the details, but she always collected crumbs of bread from the table and hoarded supplies, fearing a repeat of the famine. She used to say: “As long as there’s no war.” She lived through the war, worked as a field nurse, rescued the wounded from battlefields, and provided them with care. Grandma, if only you knew…

seeyo_u0o

My great-grandmother was a child during the Holodomor. Their mother would tear off acacia leaves, chop them, and anything that came along in the leaves—bugs or worms—was also eaten. What saved them was that a neighbor had a goat, which she hid either in a cellar or elsewhere. That woman shared milk with the children. The entire village protected that goat as best they could and valued it greatly.

larina3219

My great-grandfather went to the forest to gather firewood and never returned. The family waited for him in vain. A few days later, children playing with neighbors’ kids heard them say: “We ate meat, and we’re still eating it.” This was in the Poltava region, the village of Mali Budyshcha.

k_r_a_n_i_u_m

I heard the story of a woman who killed her own mother and cooked her meat to feed her three children. The grandmother herself suggested it, saying she was old and of no use, and this way, the children would survive. And because of this, they did.

alinaslpts

My great-grandmother’s entire family survived because there was a kind storekeeper in the village who allowed them to keep a little grain for the children. Unfortunately, not all of my great-grandfather’s family survived. They had many children, but those who lived through the famine mostly suffered hearing impairments. My great-grandfather also became hard of hearing.

Yesterday, my great-grandmother passed away at the age of 94. I will always remember the stories she told and pass them on to my children. In our family, bread is never thrown away, and we always have grains stocked for emergencies.

lesya_26_july

In my grandmother’s family, only she and my great-grandmother survived. The other children died of hunger. My great-grandfather was very weak and was thrown into a pit along with the deceased so that “they wouldn’t have to return for the dead a second time.”

olga_life

My great-grandfather was so hungry that he ate the bread meant for his younger brother. A few days later, the boy died. My great-grandfather carried this guilt his entire life. He always cried when he remembered his brother and repeatedly said: “I wish I had died then instead.”

vika_veritas

My great-grandmother told me how her father and other men from the village were imprisoned for picking a few ears of wheat from the fields. When he returned, he couldn’t walk anymore due to the severe beatings he endured. The food he had hoped to bring home disappeared with him.

yaroslav_lviv

My grandfather said their family hid in cellars and ate whatever they could find. My grandmother made soup from tree bark, adding scraps of potato peels. They survived only because a neighbor who worked on the collective farm occasionally brought them a bottle of milk.

nina_88_kyiv

My grandmother survived the Holodomor as a child. Her family survived because they hid some potatoes under the floorboards. My grandfather dug a hole in the house and covered it with planks. But the neighbors found out, and one day they came to “search”. During the search, my great-grandfather stood by the door with an axe, saying, “You won’t kill my children.” They still didn’t look under the floor.

polina_smile

My great-grandmother survived because there was a mill in the village, and her father and other men from the village secretly ground grain at night, risking their lives. They hid the flour in tree hollows, and at home, they baked flatbreads from flour and sawdust.

marta_heal

My great-grandfather was a shepherd and hid some of the milk he had to give to the collective farm. When the inspection came, he was caught. Fortunately, one of the inspectors turned out to be a family friend, and my great-grandfather was let go. He always said: “By a miracle, we survived.”

lidiya_soul

One time, my great-grandfather pulled a dead horse from the water after it drowned. The whole village gathered around to share the meat. From then on, they survived by cooking soup from this meat and drying the remains.

oleksii_vasyl

In my great-grandmother’s village, only one cow was left in each house, and it belonged to the collective farm, not the family. She said that older women secretly collected the manure from this cow because it sometimes contained grains.

shmatchenko.I

This tragic event touched almost everyone. My grandmother’s parents died from starvation during the Holodomor. She was only two years old then. She crawled over them, not understanding they were already dead. Her older brother and sister raised her. They ate everything they could find: rotten potatoes, anything else. I don’t even know how they survived.

liliya_kolinko

My great-grandmother Yefrosynia went through the horrors of the Holodomor while holding a small child in her arms. Her husband died in the war and never saw their daughter born.

Grandmother told stories about how grain, potatoes, and all their reserves were taken. She tried to hide at least a few grains. They boiled potato peels, ate lamb’s quarters, and made nettle porridge. It was hard to listen to, and even now, it still hurts.

I often heard from my grandmother, “The most important thing is that there is peace, and there is no war or famine.” Her story had many details, but I was young when she told them, so I only remember fragments.

Volodymyr Malyuta

My grandmother said that Soviet authorities forced children to work from morning till night in the fields, digging potatoes. The family had seven children. They went barefoot, slept dirty and hungry.

They thanked God for having some livestock: one cow for the whole family. They somehow got flour, kneaded dough, and baked bread.

They prayed to Jesus Christ because my grandfather used to say, “Prayer bends iron.”

Military serviceman of the International Legion for the Defense of Ukraine with the call sign “Paradox” is the crew commander of the American M113 armored personnel carrier. He is a master at using it and is constantly improving, because the legionnaire’s skills are tested every day in battle. You have to drive to the front lines, often under artillery fire and drone attacks.

Notorious supporter of the concept “in order for a cow to eat less and give more milk, it needs to be fed less and milked more” “Servant of the People” Danylo Hetmantsev, under the guise of “business requirements”, registered a draft law on the collection of VAT on all foreign purchases, regardless of their value. In other words, every Ukrainian, buying goods of any value and purpose abroad, when sending them to Ukraine, will have to pay an additional fifth part, or 20% of the cost of the goods.

When Russian missiles began barraging Ukrainian cities in the first moments of the full-scale invasion,…

On the last Saturday of November, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Holodomor of 1932–1933…

By Vladyslava Chorna, Bukvy Editor-in-Chief Otar Dovzhenko, a media researcher, creative director of the Lviv…