‘We need to re-think this Soviet-era black hole” – Ukrainian artist Veronika Harchenko

Kyiv native artist Veronika Hapchenko studied puppet theater scenography at the Kyiv National University of Theatre, Film, and Television. She dropped out of school realizing her future job could be overshadowed by theater director ideas. She is currently working in Poland, where she obtained a master’s degree in painting from the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts. She actively participates in various international contemporary art exhibitions.

Her artistic practice draws heavily from philosophical, literary, and historical research on Soviet art, which often combines the ideas of esotericism and militarism. In her work, Veronika studies the legends and taboos surrounding political leaders and iconic revolutionary artists, deconstructing and reimaging them through a uniquely Ukrainian lens.

This year, Veronika represents Ukraine at the international contemporary art exhibition Viennacontemporary 2024 in Vienna.

The artist spoke with Bukvy‘s Editor-in-Chief, Vladyslava Chorna, about her art, views on the war, and the legacy of Soviet totalitarianism.

Let’s start with the bigger picture. What does it mean for you to represent Ukraine at such a major international event?

This project, titled Energy, is international so the curator obviously couldn’t leave out Ukrainian artists, especially now when our country is at the center of global attention. Having Ukrainian artists on the art event program must be a normal thing.

Can you tell us more about the works you’re presenting and how they connect to this year’s exhibition theme?

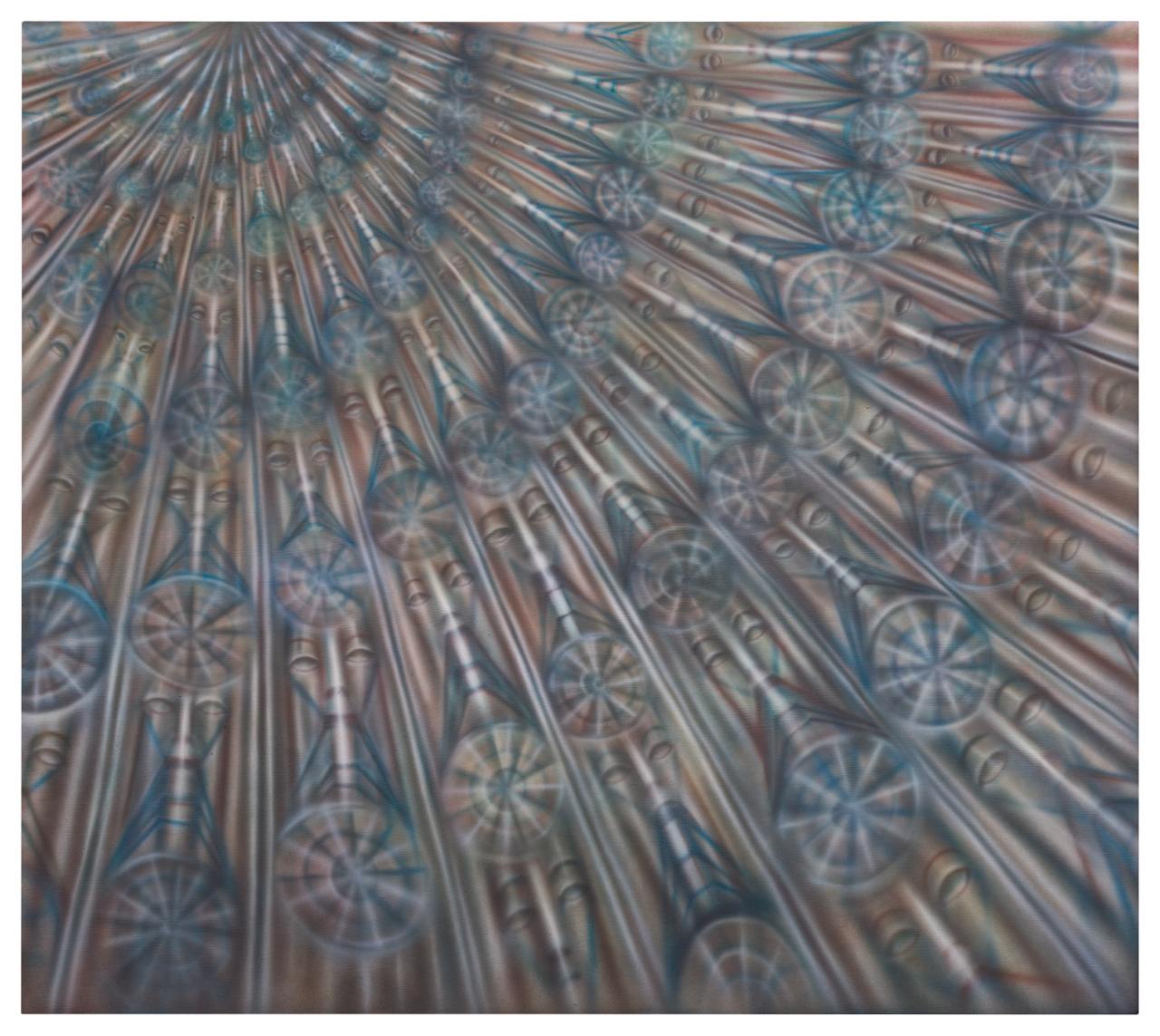

The main theme of this exhibition is Energy, and my works are divided into two cycles. The first relates to my interest in the five mosaic panels by Ivan Lytovchenko, he created for the city of Pripyat just three years before the Chernobyl disaster. The concept of atomic energy was crucial to Soviet mythology – it symbolized bringing light into the homes of Soviet citizens, the light of science to the darkness of ignorance. This narrative was strongly present in Pripyat, especially in Lytovchenko’s mosaics. In one of them, [Maksym Gorky’s] Danko rips his chest open and pulls out his heart to light the way for his people. These complex patterns make Lytovchenko’s work so appealing. We see Soviet-era mythology expressed in visual language typical of the Thaw period, when Ukrainian artists started to to pick up ideas from the early 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde.

In these mosaics, we see figures from ancient Greece, like Demeter and Danko/Prometheus. The Ukrainian intelligentsia often compared themselves to ancient Greece, resisting the Roman Empire, much like they resisted the Russian Empire. Finally, there are apocalyptic scenes, piercing through the sad, fearful eyes of the people depicted, as if foretelling the catastrophe that would soon follow.

The Chernobyl disaster has left a lasting footprint on the Ukrainian society. It placed us at the center of these tragic events that changed the world in a short time, forcing a global shift in the perception of energy and its production. In some way, this event also foreshadowed the collapse of the USSR.

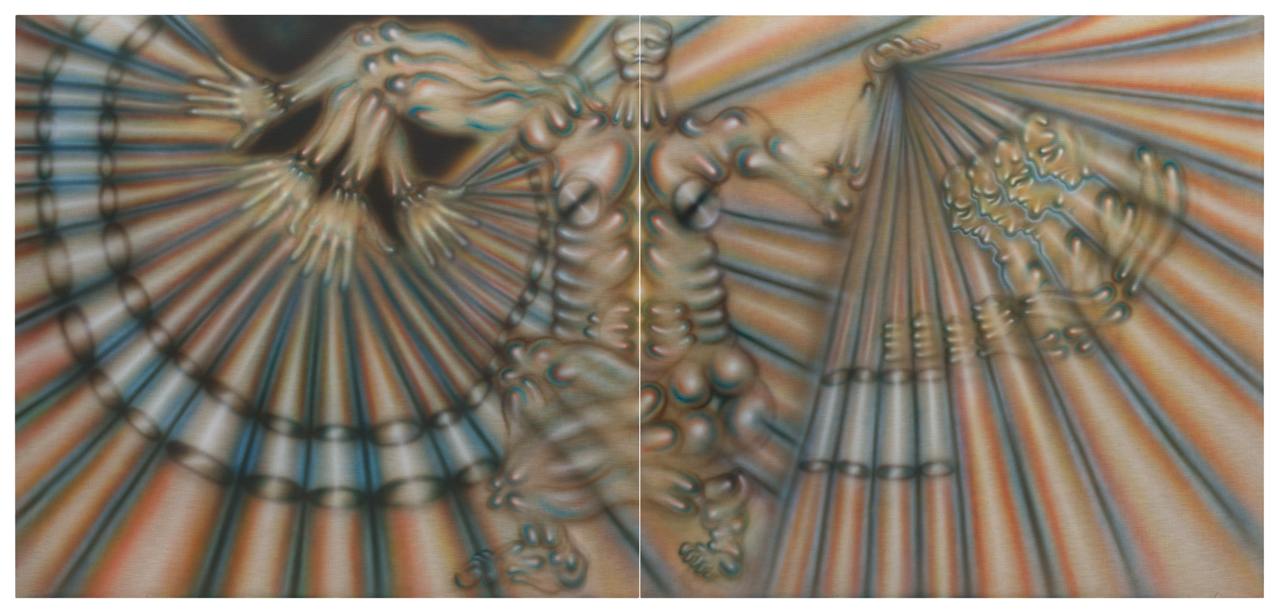

My second cycle of works revisits Soviet megaprojects of the 1930s, particularly the plan to reverse the flow of rivers. The Soviet Union’s wanted basically to redirect rivers toward the dried-out farmlands of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

I’m interested in the phenomenon of “distorted memory” surrounding this historical episode. I aim to show how the Soviet Union is remembered as a totalitarian machine that sought to “reform” both people and nature. The Soviet regime even tried to reverse the flow of rivers, as if it could alter the course of time itself, to demonstrate dominance over nature. Ironically, this intervention led to even more severe droughts.

Your work seems to frequently revolve around rethinking the destructive, totalitarian role of the Soviet Union, which impacted both people and nature.

Yes, it’s important for me to analyze if these key Soviet-era events were real or fabricated because we continue to see their ‘legacy’ in the present. We need to build complex narratives without erasing our experience.

When we talk about Ukraine’s evolution, we often recall its early 20th-century formation, followed by a large “black void” called the USSR, and then the revival of independence.

I believe we need to rethink, experience, and let go of this large traumatizing experience we had for many decades. It will help up move forward.

Do you view it was a traumatic experience for the nation?

Yes, as a colonial trauma.

Does your art respond to modern trends among young people who are drawn to the idyll of communism, who either idolize the Soviet Union or claim that the USSR only failed because it was “the wrong kind of communism”?

I believe this “romanticization” of the Soviet Union has become mainstream, including claims that Lenin and Stalin were “not so bad,” and it overshadows the traumatic experience of the nations that had to survive under the Soviet rule.

We must explain that the USSR was an empire that used the guise of “united nations and friendship among peoples” to occupy large territories and oppress many nations. Essentially, it turned them into colonies, with Moscow at the center. When discussing the fate of the oppressed peoples, we must always emphasize that the past saw the attempt to erase their identities. We know that the Soviet person was equated with the Russian person, while others were seen as inferio, automatically relegated to sub classes or even considered enemies.

We need to have an open conversation about it. Even when I was studying in Vienna, people would ask me to “bring us a Lenin statue when I was going home for a visit home. I didn’t even know how to respond to it because we had just gone through the process of toppling Lenin statues.

Do you stay in touch with other Ukrainian artists? Since the start of the full-scale war, how has the attitude towards them changed? What challenges or opportunities have emerged for them?

Huge opportunities have opened up because not many people were at the heart of the events. The way history unfolds will depend on Ukraine, primarily on our soldiers, and later on everyone else. Everyone carries their share of responsibility.

Rinat Akhmetov’s military initiative, “Steel Front”, has delivered a batch of drones worth UAH 214 million to the 1st “Azov” Corps of the National Guard of Ukraine. This shipment is part of the Metinvest Group’s ongoing support for the unit in 2025.

On October 6, the Administrative Cassation Court within the Supreme Court of Ukraine continued hearing case No. 990/80/25, in which the fifth President and leader of the party “European Solidarity”, Petro Poroshenko, seeks to have Presidential Decree No. 81/2025 from February 12, 2025 — enacting sanctions by the decision of the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC) — declared illegal and annulled. The plaintiff claims the document was falsified and that the sanctions are a tool of political persecution of the opposition, contrary to international norms. Government representatives deny the allegations and insist their actions were lawful. Journalists of Bukvy were present at the hearing.

Rinat Akhmetov’s Metinvest Group has completed the construction of an upgraded underground NATO Role 2 hospital in one of the hottest sectors of the frontline. This is the second stabilization point established under the Steel Front initiative in cooperation with the Medical Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. The new facility, funded by Metinvest with an investment of UAH 21 million, is more secure than the first one thanks to its deeper location underground (over 6 meters) and additional fortifications.

Five armored vehicles “Kozak” have received a new mission – thanks to the support of Metinvest, they have been upgraded to full-fledged command and staff vehicles. These upgraded vehicles are now operating on the front line.

A kamikaze drone flies directly toward an armored personnel carrier. But instead of penetrating the hull, it explodes on a steel screen. The crew survives. This is the new reality for Ukrainian forces, who have received enhanced protection thanks to the Metinvest project within “Steel Front of Rinat Akhmetov”.